Medieval people went on pilgrimage for many reasons (e.g. seeking forgiveness, gratitude for favours received, as punishment etc.), but you’d be forgiven for thinking that theft would not be a motivating factor. After all, why would a devout person go on pilgrimage with the express aim of stealing, and especially to steal something holy?

But robbing relics – especially the corporal remains of saints – was serious business in the middle ages and for many pious people (and not just habitual/professional thieves) it was perfectly acceptable and even commendable. They justified it saying that the saints were perfectly capable of defending themselves, so if they didn’t want to go, the ‘thief’ would not succeed; if he/she did succeed, it was a sign that the saint wanted to be venerated elsewhere. Naturally the saint’s followers didn’t want to burden their heavenly patrons with such tough decisions, and in the larger cult centres armed guards were posted within churches.

In his The Age of Pilgrimage, Jonathan Sumption recounts the story of the twelfth-century St Hugh of Lincoln who literally bit off more than he could chew. On being presented with the bandaged arm of St Mary Magdalene at a monastery he was visiting, Hugh whipped out a knife, sliced open the packaging and tried in vain to hack a bit off. Was Mary happy where she was? Apparently not, as Hugh – undeterred by his initial failure – bit down on one of the fingers and finally cracked off a few chunks with his molars. His justification to his horrified hosts? Well, he had the Eucharist in his mouth not long ago, so if he could swallow the body of Christ, then surely it was no biggie to gnaw at the bones of a saint.[1]

Others were a bit more subtle than the saintly Hugh, and eschewed treating the corporal remains of the holy dead like strips of tough beef jerky. Take for example Fulk Nerra of Anjou (d. 1040), the first great castle-builder of Western Europe, ancestor of the Plantagenet kings of England, and three-/four-time pilgrim to Jerusalem. After making the perilous journey from western France to the Holy land, he demonstrated his devotion by kissing the True Cross, and pulled away with a splinter in his teeth.[2]

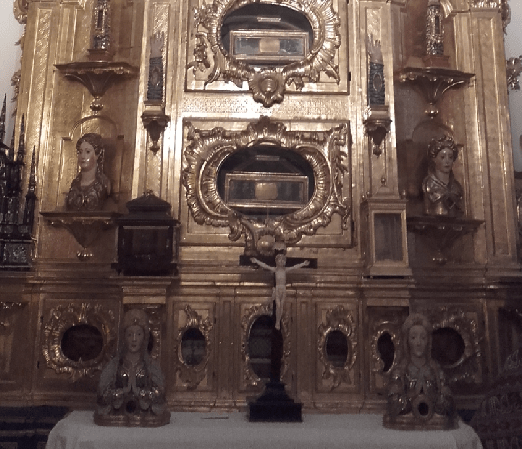

At the early thirteenth-century Lateran Council, it was decided that exposed relics were too mouth-watering a temptation and henceforth they should only be displayed within reliquaries. The most impressive collection of these on the Camino is the eighteenth-century Chapel of the Relics in Burgos Cathedral. As is common, many of these reliquaries have little windows in them, so that the faithful could see the venerated item or at least verify that there was something there. The message is plain: look with your eyes, not with your mouth!

[1] Jonathan Sumption, The Age of Pilgrimage: the Medieval Journey to God (Mahwah, New Jersey, 2003), 40–1. (Originally published as Pilgrimage (London, 1975)).

[2] Ibid., 36.