The recent passing of John Brierley, the author of some of the most popular and high-quality guidebooks to the Camino, had me thinking about guides and guidebooks. I was in Santiago de Compostela in June, finishing the Camino Francés that I began in 2021, and had two contrasting guide experiences.

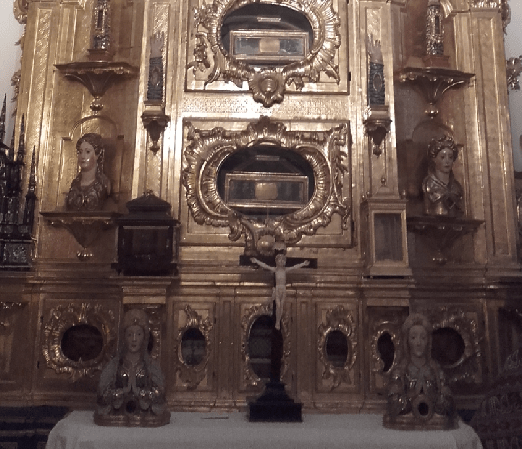

I bought a guidebook in the Cathedral shop (ok I bought a few books there), and here’s an excerpt from its description of the seventeenth-century Chapel of Christ of Burgos:

“It is a noble proto-Baroque construction with a portal with double columns on dies to hold the founder’s shield in the attic. It has a Grecian groundplan and an architraved structure with great fluted pilasters supporting double coffered arches. The dome has pendentives bearing Carillo’s arms and ribs worked to form shells pouring water”.[1]

I have a PhD in medieval history and have occasionally taught on related architecture, but even if I did recognise all the terms (recognise ‘yes’, remember/be able to explain, ‘no’), it doesn’t make for exciting reading. I found myself in agreement with the great Renaissance writer Michel de Montaigne:

“I cannot tell if others feel as I do, but when I hear our architects inflating their importance with big words such as pilasters, architraves, cornices, Corinthia style or Doric style, I cannot stop my thoughts from suddenly dwelling the magic palaces of Apollidon: yet their deeds concern the wretched parts of my kitchen-door!”[2]

Ok, so the Chapel of Christ of Burgos is a little more impressive than the kitchen door of my flat, but you get the point. It’s all very well to complain, but how would I do it differently? I think if I were to author a guidebook to the Cathedral, I’d begin by taking a particular feature (e.g. a single chapel) and use it to explain the terminology, and architectural and artistic ideas that are found in other parts of the building e.g. this is a ‘pilaster’ a decoration against a wall that’s designed to look like a column, but actually just for show and not holding anything up. It’s the teacher in me coming out. Teach them what they’re looking at first, and then help them discover the same elsewhere themselves.

My second guide experience was with a live guide, taking the Cathedral rooftop tour, such a bargain at €8! It’s not for those who suffer from fear of heights, and you need to be mobile, but for everyone else I’d recommend it. With a radio-earphone connection the young lady guiding us led us around the ongoing roof works, discussing the competing needs of conservation and desire for accessibility, explaining functions and design ideologies, connecting us with the parts of the cathedral directly below, sharing how some of the Camino practices of today (e.g. burning items of clothing in Finisterre) link with both the history and features of the cathedral, etc. All in all, even though I probably only followed about 90% of it (it was in Spanish), it was the best guided tour I’ve ever had in Spain.

[1] Alejandro Barral and Ramón Yzquierdo (trans. Gordon Keitch), Santiago Cathedral: A Guide to its Art Treasures (5th edition, 2019), p. 92.

[2] ‘On the Vanity of Words’, in Michel de Montaigne (trans. M.A. Screech), The Complete Essays (London, 1991), p. 343.